Jamel Shabazz for French Fries Magazine issue 5

Interview by Margherita Pincioni

Jamel Shabazz was born and raised in Brooklyn, New York. At the young age of fifteen, he picked up his first camera and started his photographic journey. Since the early 1980s, Shabazz has captured the energy of street life in New York, making iconic images of community, joy, and style. The solo show "Photographs by Jamel Shabazz: 1980–1989" at Galerie Bene Taschen, Cologne brings together mostly unseen works from this era. Shabazz was one of the first photographers to document the emerging youth culture, along with his own experiences, in neighborhoods across East Flatbush, Bedford-Stuyvesant, downtown Brooklyn, up to Times Square. Capturing a time long gone from our collective culture and a wide range of social conditions, Shabazz made the streets of New York and the city's subway system the backdrop for many of his iconic photographs.

Shabazz has exhibited his homegrown approach to portraiture everywhere from the Rockefeller Plaza in New York and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the Addis Foto Fest in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. His work is part of the permanent collections at the Whitney Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture, and the Fashion Institute of Technology. His books "Back in the Days" and "A Time Before Crack" are considered classics for their articulation of a visual vernacular and continue to inspire young generations of photographers.

Your father had a large library of books, which ones impressed you the most?

The ones that I took the most inspiration from were a collection of books from TIME/LIFE Photography publications. In total, there were about 17 books and they served as my formal introduction to photography. Each book focused on a particular theme, from great photographers, printmaking, and documentary photography to photographing children to name a few.

How much power did your family photos have in your education?

The power that the family photos and photo albums had on my educational development was that they produced a curiosity to learn more about all of my family members; mainly the men who all served in The United States military in different theaters. For example, my paternal grandfather served in World War II and in those albums, there were a series of black and white 4 x 6 “ prints of him in uniform. The back of those photos indicated that he was stationed in Burma and the year they were taken was in 1944. Seeing that, along with the distinct unit military patch that he wore on his uniform, inspired me to start researching as much as I could about that war in the Pacific and the role that African Americans played in that conflict. I would go on to do similar research on my father, who enlisted in the US Navy in 1955, at the age of 17 and traveled throughout the Mediterranean on the USS Intrepid Aircraft carrier. It is from his personal journey that I learned about Greece, Italy, Spain, Norway, and a number of other European nations.

Which camera did you start working with? Do you remember the first photo you took?

I started with a Kodak Instamatic 126 point and shot camera that I borrowed from my mother. I cannot recall the first actual photo, but there is a good chance it was a color snapshot of my best friend in front of our junior high school in East Flatbush, Brooklyn during the spring of 1975.

You once said: “My journey has never been about wanting to be a photographer. The primary vision was to save our people”, what did you mean?

When I first picked up the camera it was for fun, but as I entered the 1980s and so many young lives were senselessly being taken around me, I had to reevaluate my mission and purpose in life. It was at that point that I realized I had a higher calling and it was to be a source of light and inspiration to the younger generation in hopes that I could offer them some guidance to help them overcome the many challenges they were facing. Some of the major issues we had to contend with were the AIDS and crack epidemics and the war on drugs. I was watching the destruction of my community as well as others suffer and I just could not sit idly by without trying to lend my voice to save lives. Having a camera provided me with an entry into the lives of the folks that I wanted to communicate with, but the bigger picture was trying to guide young people in a better direction. Back then I would use my platform to speak about issues such as the importance of health and nutrients, education, job security, knowledge of self, and the need to be mindful of the many obstacles and traps that they would be encountering during those troubling times.

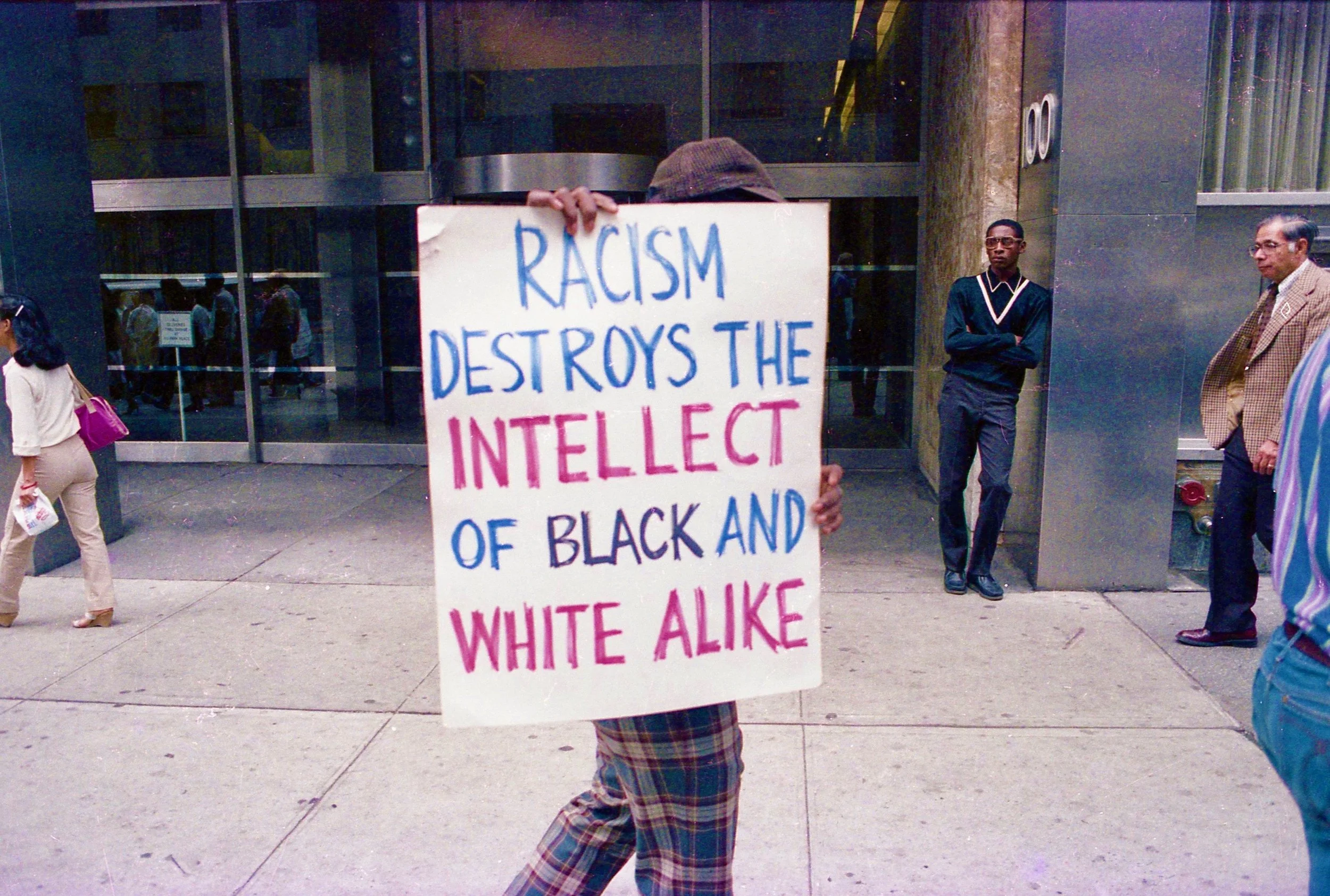

Sign of the time, NYC 1981

During the pandemic you started posting on Instagram, what feedback did you get from the social media audience?

The feedback was beyond anything I could have ever imagined. I was receiving direct messages from people around the world, who had a deep appreciation for the images and the occasional inspirational quotes that I felt compelled to share. It was my desire to offer some degree of hope and comfort during a very challenging time when so many people were confined to their homes. Aside from those comments, a number of people from New York City were writing to me, giving accounts of their personal relationships to some of the photographs I was sharing. One young woman wrote to me after I posted a photograph of a father and his twin sons. She said, that the gentleman in the photo was her father and the two young boys in the image were her brothers, who were both murdered years apart and how her father is still mourning their loss today. In countless other comments, folks told me that they looked forward to my daily posts, as my images made their hearts smile.

"Rush Hour", taken in 1988, has become a symbol of the aesthetics of those years. It doesn't happen so often that a photo is able to summarize the aesthetics of an era, can you tell us about it?

Actually the year is 1980 and that particular photo like so many others was just a serendipitous occasion. I was in the right place at the right time, with my camera at the ready searching to photograph something special during the morning rush hour. It was most significant, because the 1980s was a very special decade for me, as I had just returned on the scene, after coming back from where I was stationed in Germany, completing my enlistment in the Army. I was young and eager to take in all the vibrations of New York that I have been missing for 3 years. Now back, with a camera and fresh eyes, I was eager to document this new decade, from everyday life to the various communities that made New York one of the greatest cities in the world.

Your photos are not meant to covertly capture a simple portrait of an unaware subject; is it about collaborating with the person, almost a conversation about what is happening at that moment?

In most cases there was a conversation between me and the other person or people that I wanted to photograph and the exchange would vary depending on who I was speaking with. For the most part, I would briefly explain who I was and my intentions. If time would allow, I would show them sample images from a portfolio I always carried with me. There were also occasions that the conversations would go on for hours, discussing everything from photography to current events. Most were positive and reassuring.

Joy Riding, Flatbush, Brooklyn 1981 © Jamel Shabazz + Courtesy Galerie Bene Taschen

When did your photographs start capturing the attention of the media?

Around 1999, my photographs were featured in two popular magazines here in the US. One was the Hip Hop magazine “The Source”, that gave me a 10 page spread in their 100th anniversary issue. That one publication was so well received; due in part to my work, it sold out almost immediately once it hit the newsstands. And the other was a New York based International magazine called “TRACE”. It was through that magazine, that my photographs were introduced to a wider global audience.

Can you tell us what life was like in Brooklyn in the 80s?

The best way to sum up the 1980s was bittersweet. I returned back to my hometown of Brooklyn very hopeful and optimistic. It was a new era of high fashion, conscious music and hope, but once I started to settle back down, I was being informed by friends, of the conflict that had transpired just a few months prior to me coming home from the service. I learned that there were ongoing wars in the neighborhood and that a number of my friends had been shot by rivals. Within a short span of time, a few of my close friends lost their younger brothers to violence, young men who I knew personally and had photographed many, prior to being murdered. And then came the AIDS and Crack epidemics and everything seemed to change overnight. Countless lives were now being compromised and so many people lost their souls and many their lives. During this same time, the president declared a war on drugs and the crisis intensified, as families were disjoined, friends became enemies, and correctional intuitions and graveyards filled up.

You are one of these subjects yourself, as part of this community that you photograph. Do you think it was easier to capture its essence because of that?

Being from the community and having an understanding of the culture and its residents definitely made the process of documenting easier.

Friends, Bed Stuy, Brooklyn, NYC, 1981 © Jamel Shabazz + Courtesy Galerie Bene Taschen

The absolute protagonists are boys and girls, do you think it's because they want to let people know who they are, as an affirmation and confirmation of their image?

I would have to agree with that statement. During the time I was photographing youth culture, everyone for the most part, were individuals who wanted to be seen and validated.

There is no denunciation or condemnation, much less a moralistic vision, what is the purpose of your images?

The images that I have documented over the years serve many purposes. One was to have a visual record of all of the people and situations I encountered during my life, the second was to build friendships and relationships, third was to make sure that those who I shot had good photos of themselves, and lastly to make sure that my community and the larger world communities have a place both in history books and museums.

You have declared fans among fashion designers, but you don't follow fashion. How is your relationship with this world?

My relationship with the fashion world goes back 40 years. So much of my earlier inspiration came from fashion photographers, such as Helmut Newton, Gordon Parks, Keith Major, and Barron Claiborne to name a few and since the mid-1970s I have been reading and studying GQ Magazine. Besides street & documentary photography, I also have a deep love for fashion photography. Little is known about the clothes that I have been designing since the mid-1980s, but back in those days I would purchase yards of 120 superfine wool and custom made buttons and take these items to a local tailor. I created my own style of dress and many of my fashion images are of my models wearing my designs. I never had any direct ties to the fashion world so I was never able to gain great traction, however I still have all of these clothes. The Fashion Institute of Technology does have some of my images in their permanent collection and today I am good friends with the great fashion designer Dapper Dan; for me that is enough.

Young Love, Downtown Brooklyn NY, 1983 © Jamel Shabazz + Courtesy Galerie Bene Taschen