“I’m all over the place”, american artist Katherine Hubbard, interview by Ally Ferraro

Interview Ally Ferraro

Editor Maja Bebber

Photography Christian DeFonte

Katherine Hubbard is an interdisciplinary artist whose work engages the intersections of photography, performance and text. Using analogue photography and experimental darkroom practices, Hubbard asks how photographs procedures might be called upon to investigate social politics, history, and narrative. In her photographs the physical positioning of one’s body has an essential relationship to how one processes images, exploring this encounter as a time based experience. Hubbard’s writing practice forms the core of her performances.

Hubbard received her MFA in 2010 from the Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts at Bard College and is currently an Associate Professor of Art and MFA Graduate Director at Carnegie Mellon University School of Art.

Hubbard’s performances have been presented at the Chinati Foundation, Marfa, Texas; Konstfack, Stockholm, Sweden; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Her work is included as part of the permanent collection at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

With French Fries Magazine, she opens up about her craft, her exhibition ‚the Great Room’ and her deep and close relationship with her mum.

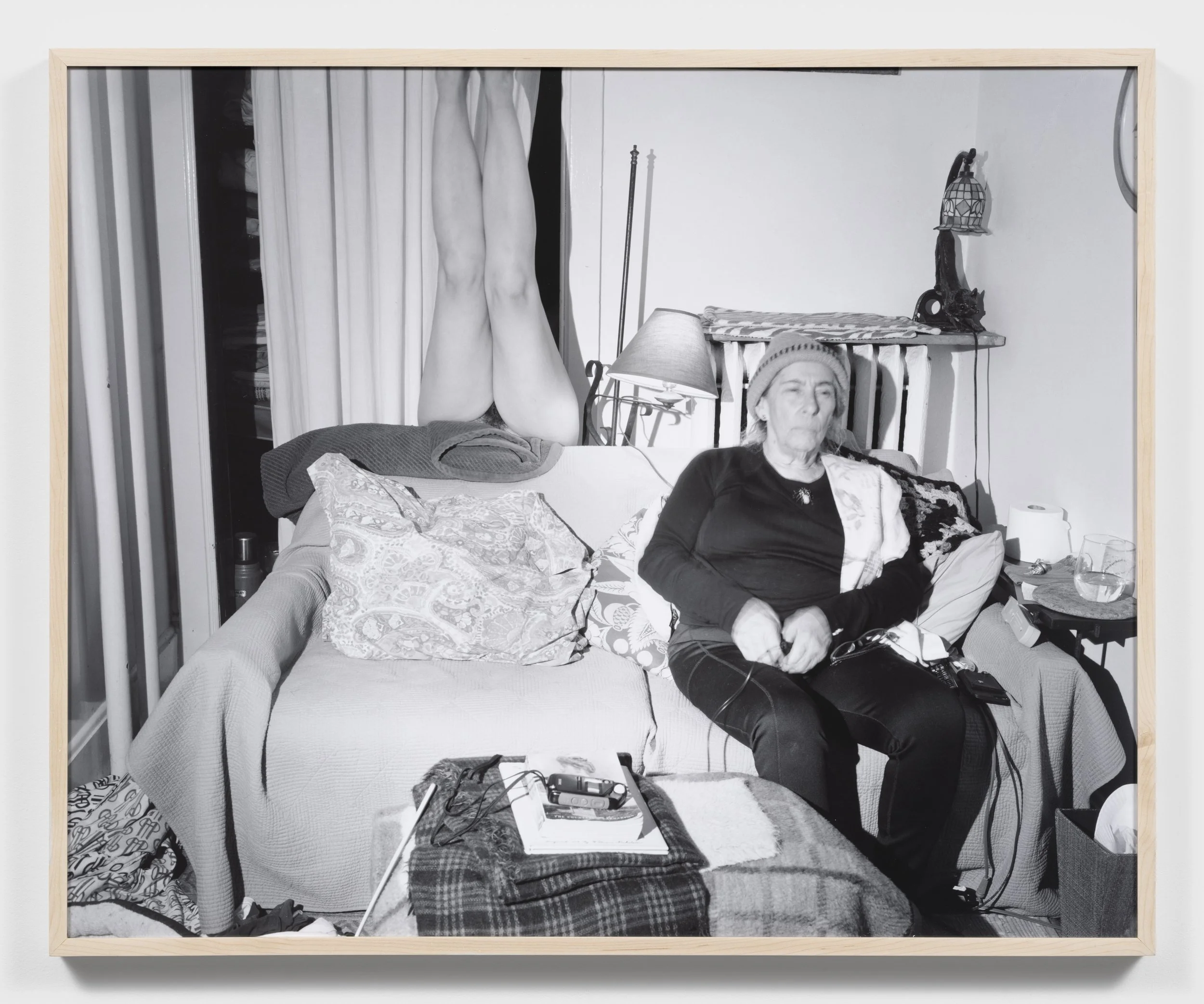

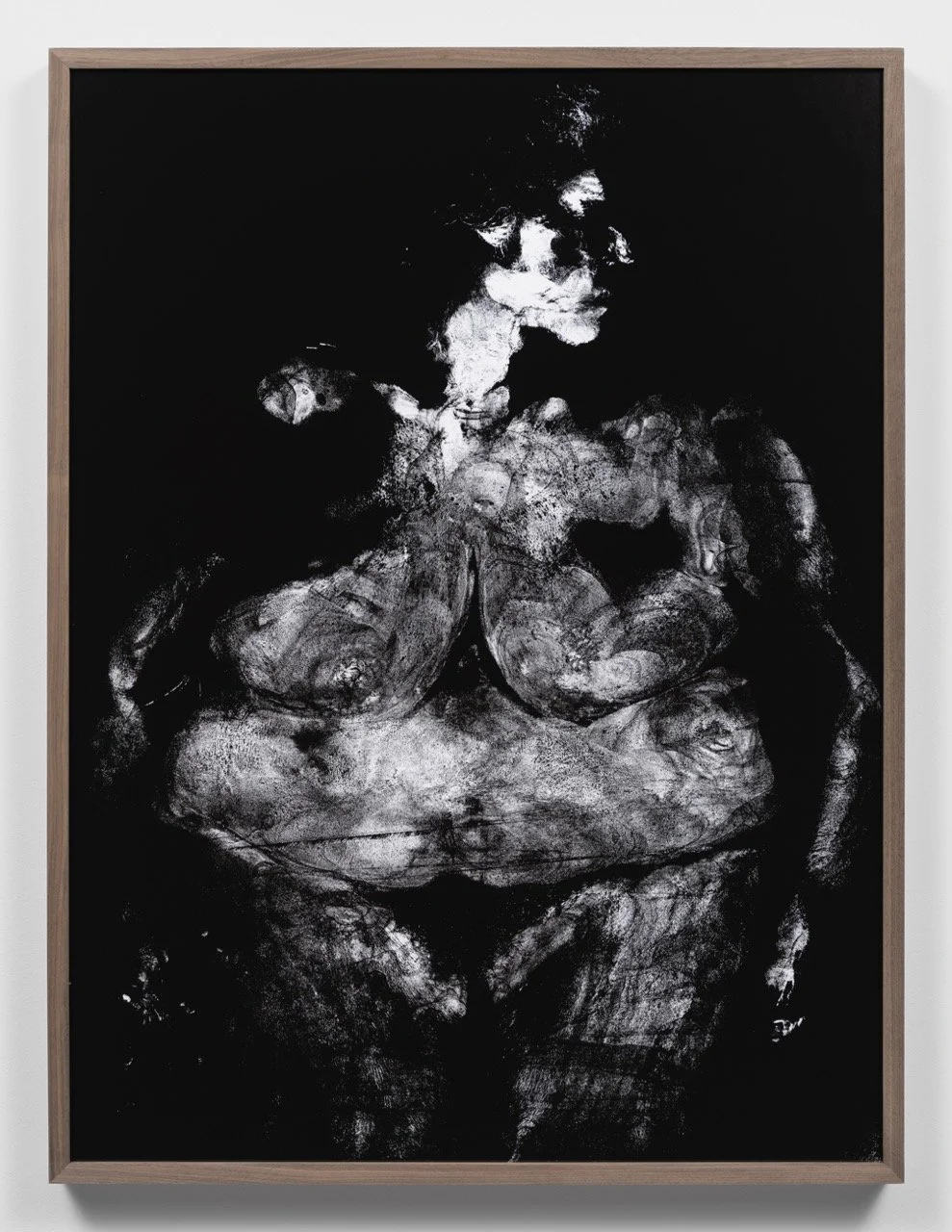

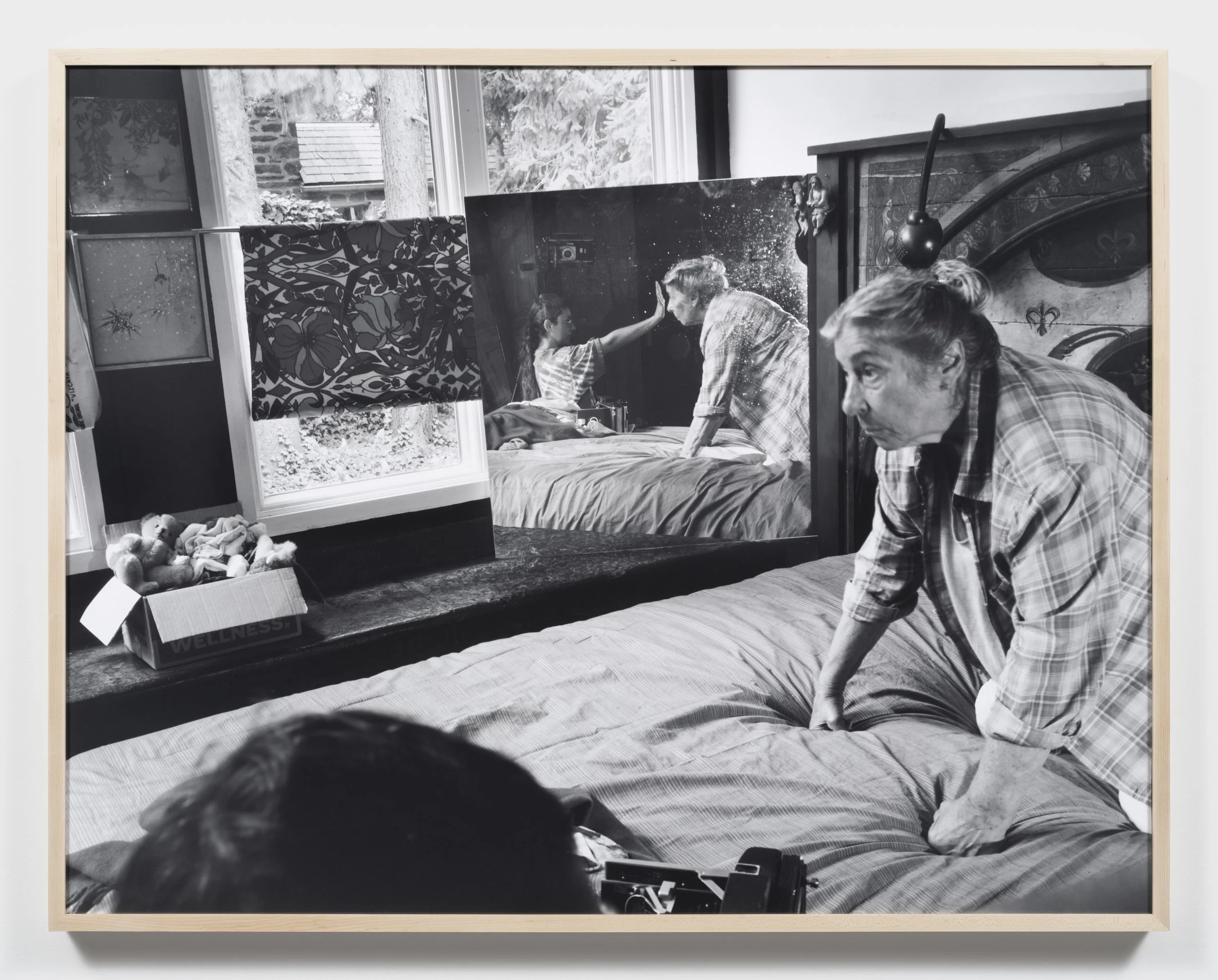

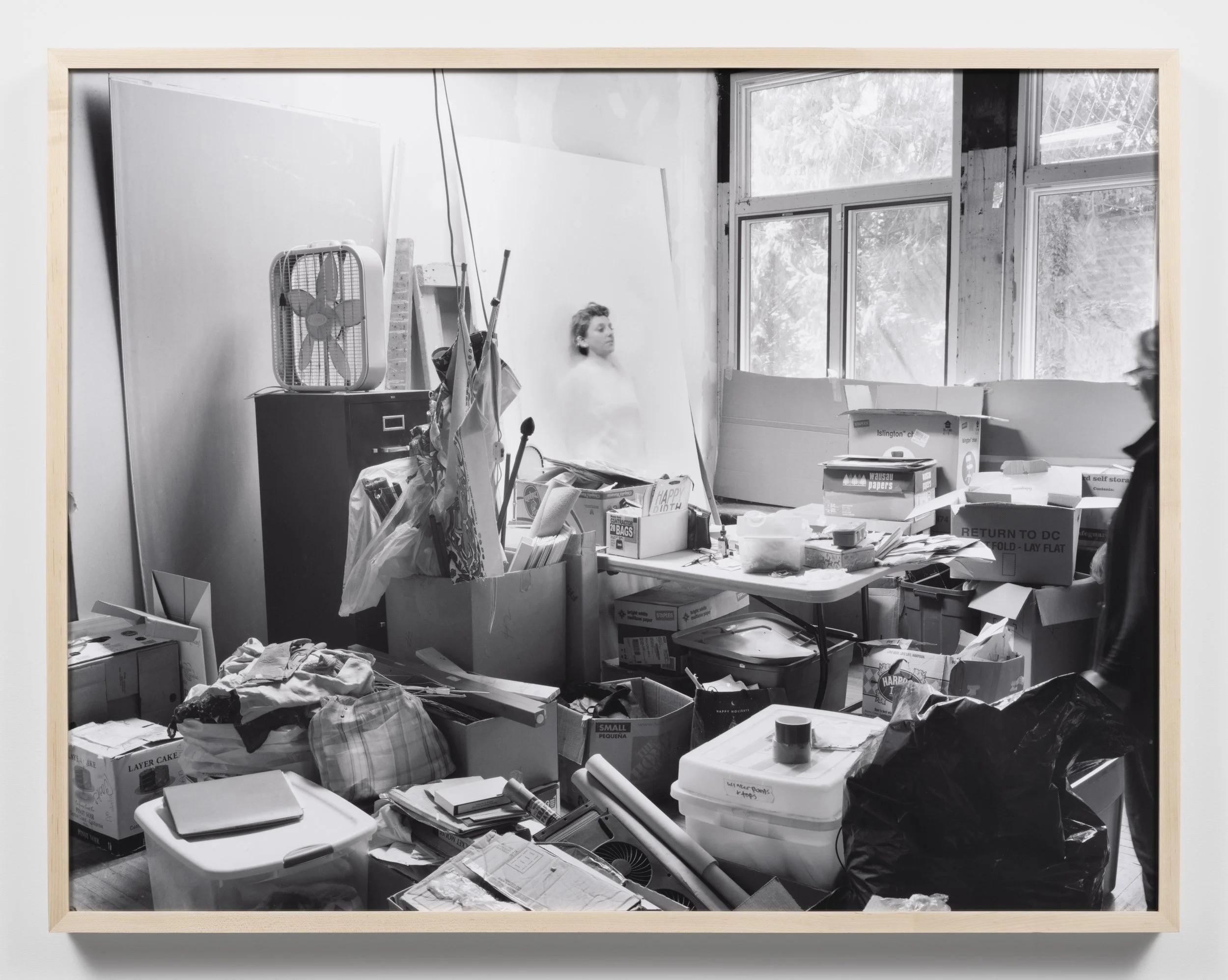

Katherine Hubbard, The Great Room

Katherine Hubbard, The Great Room

You live in New York right?

I live in upstate New York with my wife most of the year, but I work in Pitts-burgh. I'm the director of the MFA pro-gram at Carnegie Mellon so I live in Pitts-burgh during the academic year, and the rest of the time I'm between New York City and upstate New York.

I'm all over the place.

Are you in Pittsburgh right now?

Yeah, I'm in my office.

What is Pittsburgh like? I've always been very curious.

It’s a great city, very green with lots of parks, and it’s fairly working class. There's very bad fashion, which is disappointing but you can't have it all.

Are you born in America?

Yes, I was born in Philadelphia.

The great room. It is real?

I've been making photographs with my mom for about three years since she was diagnosed with a brain disease called LATE and early-stage dementia. So, I've been making photographs with her throughout this phase of her illness that I think people don't talk about very often. It's the part of the illness where many things are unknown and you’re still learning how someone will change. It’s a phase that isn’t marked by extremes but seems to perpetuate this general haze of confusion. I think the stigma of illness generally makes us imagine people with dementia only in extremes and the word dementia becomes this generic stand in for memory loss, but this work is about all the time spent with my mom throughout this slow evolution. I spent a lot of time paying attention to how my mom was changing and paying attention to the ways that memory is interwoven with emotionality and one’s sense of personhood.

Did you live together?

No, my mom lives in Philadelphia, PA, so, I drive back and forth to Philadelphia all the time to be with her and take care of her. My mom is also the first person I’ve ever photographed. The work is very much about our relationship and women's work by extension —the work of being a daughter. It's about care work, and it's about very ordinary things, very ordinary daily life. Many of the photographs that I make with my mom, they're made while we're doing her daily routine rituals like watching the news, bathing, and organizing paperwork. One of the reasons I started making photographs with her is because as her illness progressed I realised that my capacity to be both an artist and caretaker were at odds with each other and I didn’t have enough time to do all of the things that this phase of my life demands of me. In working with my mom on this series of photographs I have started to think about photography itself as a form of care work because of the time that the medium allows my mom and I to share. The camera's this tool that I have and can take with me anywhere, it’s a way to be in relation to other things and people and it creates its own form of sociality.

You give everything. I understand what you mean.

And for me, the question about time as a resource has a lot to do with class. When I'm with my mom and we're making photographs, it has to be an active and conscious decision to do so, to spend time making photographs instead of taking care of all the other things that need to get done. And so, I think about that time making photos as this essential break from this other kind of time we have which is really spent in life management mode. When we make photographs, we don’t have to be rational or make sense, we don’t have to make a particular kind of image and in that time, something fantastical emerges. We're not paying bills or food shopping, making food or prepping medication. We're not doing all the stuff of life that's so driven by rigidity, capitalism and all these other frameworks that we build contemporary life around. Making photos gives us back this other time where we can be weird, It's this way to pause all this pressure for her to remain cognizant. It’s a form of care for both of us that gives us back something in the relationship that's easy to lose when you're with somebody who has a degenerative brain disease. My mom knows that she has dementia, and she is self-aware that everything is changing for her.

I developed a way of making photographs with my mom that's entirely distinct from how I've ever used a camera in the past. There's a lot of formal decision-making that became intuitive the longer we worked together. For example, I started to reflect multiple spaces into the photograph through mirrors in the house or using deep space, shooting through multiple opened doorways to exaggerate the length of my mom’s apartment where she lives. I wanted to build very deep space and imply tunnels, passageways or doorways, to complicate the spatiality within the photograph. I've developed this way of being in my mom's space that I think of as homoeopathic in the sense that when there's something uncomfortable for me such as piles and piles of clothes, instead of trying to fix it or make it go away, which is my impulse, I do the exact opposite within the photograph, I started to build more chaos into the space with mirrors or opening the door and let-ting even more layers of that spatial confusion be part of the image. I'm so uncomfortable when I'm there but if I think of my mom’s home as a stage It completely changes my ability to be there. This way of thinking allows me to take the chaos and amplify it instead of managing it, for example I bought a bunch of tie dye tee shirts to wear while we made images because I loved the idea that in all the chaos even my clothing would be swirling, twisting and mirroring the environment of her home.

There's another very personal aspect to the decision making to build all the layering with mirrors, deep space and door-ways. All these things are there in some ways to protect my mom from the image. I have some awareness that although I am there with her and the images are incredibly personal and incredibly revealing, the-re's something for me in the process of making the images where I never want the viewer to feel like it's easy to see her, or easy to get to her. And then in these rare moments that are incredibly raw and revealing certain images will be incredibly intimate and cut through all the distance that the other images intentionally create, there's one photograph of my mom in the bath-tub where she's looking directly at the camera. You can see my feet and legs in the image, so you understand that I am the photographer, but you also understand something more tender. For me this kind of image needs a lot of padding and other images to help a viewer arrive. I try to make my body as present as possible in many of the photographs. I am often reflected in mirrors or my legs or arms enter the image. For me, I want the photographer to be a present and engaged living body within the image space. I am not interested in letting the viewer feel that they are experiencing a privileged view into my mom’s world. I want the photographs to reveal their construction and I want it to be clear that I am making conscious decisions around visual access.

That's very interesting because I noticed that. And I thought of many things. I thought, how come the chaos here looks so fascinating, how can I make my house look like this? And then I noticed that it was a discovery, to see your mom. And every time I look at the photos, I discover something else that is interesting. What do you think is destructive for photography?

As an educator, I spend a lot of time talking about the history of photography, I've also spent a lot of time in various educational contexts that approach photography in incredibly different ways. So, I feel attuned to the history of photography as both an applied art and a fine art. I don’t value any particular type of photography more than any other but I think part of what makes photography fascinating and continuously relevant is how much the meaning changes depending on context. I think about the history of photography as a history of how people have looked at other people and other things. It’s a his-tory of how we have valued things around us and it’s very tied to the formulation of language. But of course as we know many of these histories are incredibly fraught be-cause People have historically looked at each other in horrifying and troubling ways. Photography is often as much about what is seen in the image as it is about everything that has been left out. So, for me, I feel like part of the work of being a photo-grapher is about being incredibly careful and critical about how I use the camera. I think there's a demand to be intentional with the camera. For me in my work it matters where you make a photograph from and every aspect of how you build the image space creates the content of the work. There is a politics to the positioning of both my mom and my bodies within the images.

Photography is a fascinating medium because it's embedded in culture. But I also think that the ways that we use photography in contemporary life are such that we’re not given the time or the space to think critically about how images are circulating. I feel aware that when I am making an exhibition, I am on some level working against the limited attention we have be-cause of how images function in so many other contexts so I also try to use the installation, pacing and rhythm of the images to slow things down.

Do you think photography can be political?

Yeah, absolutely. I think photography is almost always political.

Art for women is slowly getting more and more recognized. How do you feel about this?

As a queer woman I almost exclusively look at, think about and am inspired by women artists— women have always existed, women have or the space to think critically about how images are circulating. I feel aware that when I am making an exhibition, I am on some level working against the limited attention we have be-cause of how images function in so many other contexts so I also try to use the ins-always made art, and I think women and queer people, have a long history of celebrating their work outside of mainstream contexts. Art takes many forms and I certainly don't think that art only matters or takes form in commercial galleries or institutions. In self-selecting communities, we know how to celebrate our work and our ideas. We know our value.

Katherine Hubbard, The Great Room

Katherine Hubbard, The Great Room

Katherine Hubbard, The Great Room